What Is Intermodal Shipping? A Beginner’s Guide to Moving Freight on the Rail

If you ship full truckload freight, you should be utilizing intermodal as well — it is a key component of any shipper of choice strategy.

Intermodal shipping adds capacity, reduces transportation spend and contributes to your sustainability initiatives.

If you’re new to the mode, this article covers a few of the basics you need to know to get started.

What is Intermodal?

Intermodal shipping is the transportation of freight using multiple modes (inter = between, modal = modes).

Technically, this could include any combination of ocean, rail, truck and air.

In North America, the term “intermodal” usually refers to the combination of trucks and railroads to move freight in shipping containers (aka containerized freight). We’ll use this definition for this article.

Intermodal is a mode of freight transportation that uses a combination of trucks and trains to move shipping containers.

How Intermodal Shipping Works

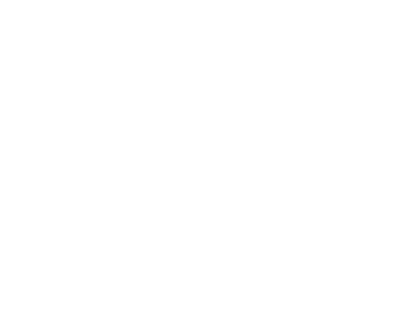

Unlike full truckload shipping, which involves one carrier who moves a load from its point of origin to its destination, an intermodal load moves in three distinct parts using three separate carriers.

The Three Parts of an Intermodal Shipment

- Part 1. Road

A specialized intermodal driver — called a drayman or drayage carrier — picks up an empty container from the origin rail ramp and brings it to the shipper. Once the drayman is loaded at the shipper, they return the container to the rail ramp. - Part 2. Rail

The railroad takes the container from the origin rail ramp to the destination rail ramp. - Part 3. Road

The destination drayage carrier picks up the container from the ramp and delivers the shipment to the receiver.

What Are the Benefits of Intermodal Shipping? 3 Reasons to Convert Truckload Freight to the Rail

Compared to full truckload shipping, intermodal is typically slower (transportation takes at least one day longer in most lanes) and more complex (it involves multiple parties).

So why do shippers use it? Let’s take a look at the core benefits.

1. Cost Savings

First and foremost, shippers use intermodal to protect their budgets.

Though savings vary by lane, seasonality and the state of the current truckload market, intermodal options are often hundreds —sometimes thousands — of dollars cheaper than truckload.

Even in lanes where intermodal is only marginally less expensive on a per-load basis, over the course of the year, the savings can add up.

2. Sustainability

How sustainable is intermodal shipping?

On average, rail shipping is four times more fuel efficient than truckload — a train can move one ton of freight 479 miles on single gallon.

In addition to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, a fully loaded intermodal train takes about 280 trucks off the road, decongesting the air and North America’s highways.

Interested in learning more about how shippers are implementing sustainability in their supply chains? Download our original, third-party research study on sustainable supply chain management.

3. Capacity

Every shipper will experience supply chain disruptions, from minor incidents to macroeconomic trends.

Incorporating intermodal into your supply chain strategy increases and diversifies capacity while reducing reliance on the truckload market, where — depending on the state of the truckload cycle — capacity is not always easy to come by.

Intermodal unlocks an entirely different source of carrier and equipment capacity.

The Class I North American railroads maintain shared equipment fleets with over 100,000 domestic 53’ containers, and there are several asset carries with thousands of their own privately-held containers.

This massive pool of equipment moves across the continent through an interconnected web of railroads, departing from and arriving at dozens of intermodal facilities, accessible in nearly every metro area.

No matter where you are, or where you are shipping to, there is a decent chance that the North American intermodal network can cover it.

How to Find Intermodal Conversion Opportunities in Your Network

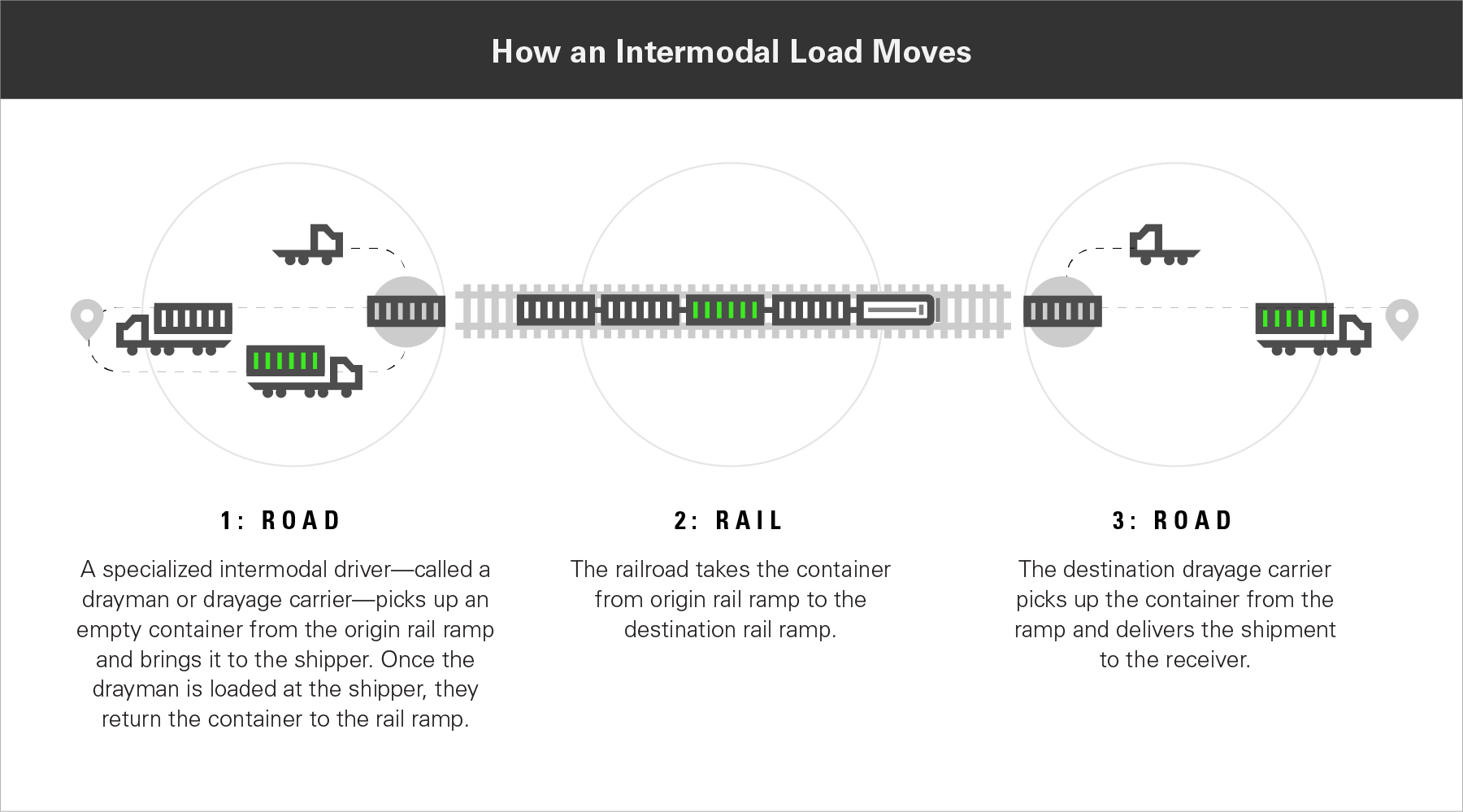

There is no hard-and-fast rule to determine which lanes are a better fit for the rail.

Several factors come into play, including:

- Total lane distance

- Proximity of origin and destination points to rail ramps

- Current truckload rates

- Rail service routing

- Underlying shipment requirements

The best way to optimize your network and find every conversion opportunity is to work with an experienced intermodal provider.

They will simplify the process and make your intermodal shipping experience as fluid as truckload shipping.

As a general rule, if the lane is longer than 500 miles and you can ship it in a 53’ dry van, it is a potential candidate for intermodal conversion.

Getting an intermodal rate is free, so it’s always worth checking.

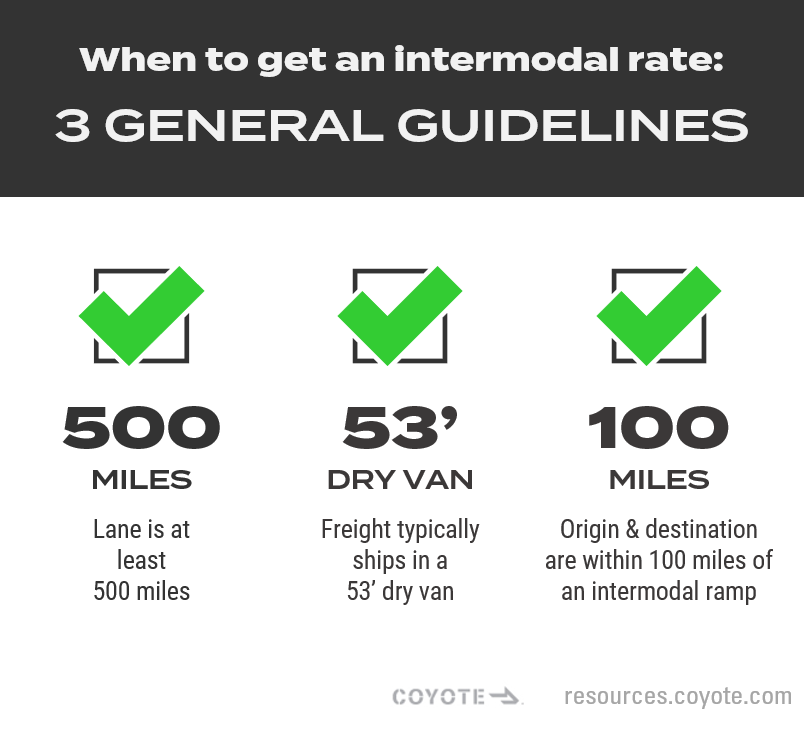

The 4 Types of Intermodal Carriers: How to Choose a Provider

Shippers cannot go directly to the railroads to move intermodal freight. Instead, they must work with an intermodal service provider.

There are a few different types of carriers that shippers can choose from, each with their own strengths and weaknesses.

Each shipper will have to decide which type is right for their business based on their supply chain — many use a blend.

Before you dive into the nuances of intermodal pricing, it’s helpful to understand how each type of intermodal provider structures their business.

Here’s an overview of the most common intermodal carrier types:

1. Non-Asset-Based Intermodal Carriers

Also called intermodal marketing companies (IMCs), these carriers are intermodal 3PLs that maintain contracts with the Class I railroads. IMCs rely on the railroads’ shared pool of +100,000 containers. Coyote, for instance, is a leading IMC.

- Pros: Provide a high degree of flexibility and provide access to the railroads’ equipment pool and a wider drayage community; Can provide all types of freight — including truckload, LTL and intermodal

- Cons: IMCs are reliant on the railroad for cost and equipment.

2. Asset-Based Intermodal Carriers

These carriers own their own fleet of intermodal containers and typically their own drayage operation (trucks, drivers, chassis, yards, etc.).

- Pros: Have a high degree of control over cost and equipment

- Cons: Limited to the physical presence of their assets, do not cover all lanes, prefer to avoid certain lanes based on network balance

3. Asset-Lite Intermodal Carriers

These carriers have access to the railroads’ equipment pool, but also own some of their own intermodal assets.

- Pros: Best of both worlds

4. Resellers

These are typically truckload brokerages that are not actual IMCs. They do not have direct relationships with the railroads, relying on asset carriers and IMCs to move their intermodal loads.

- Pros: Assuming a shipper is already working with the reseller for truckload, they don’t have add another vendor.

- Cons: Add another layer of margin to the shipper, inability to secure committed rail pricing, inability to source their own equipment, no control over drayage operations, and less visibility to the shipments in transit

Intermodal Transportation Glossary: Important Terms to Know

Intermodal is a unique mode with some of its own jargon. Here is a short glossary of terms that are helpful to know.

While this list isn’t comprehensive, it will help you start talking like an intermodal pro.

- Blocking and bracing

Intermodal transportation is smooth and steady, but the container will be lifted with cranes and subjected to gentle vibrations from hundreds of miles of railroad tracks — all of which can cause pallets to shift. To prepare the freight for intermodal transportation, shippers will use various methods to secure the pallets in place, called blocking and bracing. The most common methods are filling empty space with dunnage (often air bags or honeycomb void fillers), load bars (aka load locks), and/or 2x4s nailed in the container floor. Though shippers are responsible for blocking and bracing, there is no need to be intimidated — you do not need to build a fort in the container, and the railroad and a knowledgeable intermodal provider will help you with a reasonable loading plan. - Chassis

This is what the container is placed on for road transportation. The driver will hook up their truck to the chassis. It looks like a bed frame with wheels and a towing hitch. - Container

Also called a “box” or sometimes a “can”, this is the equipment that the freight is loaded into. Containers are either 20’, 40’, 45’ or 53’ in length, with 53’ being the most common for domestic intermodal shipping on the rail, and 20’, 40’ and 45’ used in international ocean shipping. They are made of steel, have corrugated sides and are able to be stacked on top of each other. Related: 40′ International vs. 53′ Domestic Containers, What’s the Difference? - Container Number

Sometimes called a container stencil, this is the unique identifier that is painted on the outside of each individual container. It always consists of a four-letter abbreviation (which signifies the container’s owner and ends in a “U”) followed by a six-digit serial number. For instance, a CSX-owned container might have a number of: CSXU 123456. - Containerized cargo

This is the blanket term for any freight that is loaded into shipping containers for intermodal transportation - Drayage

Also known as the “road” portion of an intermodal shipment, this trucking portion of an intermodal shipment takes the freight from the shipper to the rail at origin, and from the rail to the receiver at destination. Drayage involves a driver with just a truck (aka power unit or tractor) hooking up to a chassis/container combo and driving it a relatively short distance (usually under 100 miles). Drayage moves almost always start and/or end at an intermodal terminal or a port (sea or air). - Draymen

These are specialized carriers that handle drayage moves. They operate in-and-out of rail terminals and ports in a particular metro area — standard full truckload carriers are not allowed to enter intermodal facilities. Compared to the full truckload market, the drayage carrier base is much smaller, which can limit same-day pick up capacity. - Dry Run

This is the intermodal equivalent of a Truck Order Not Used (TONU). This occurs when a drayman arrives at a shipper or receiver and, through no fault of their own, cannot be loaded or unloaded. - In-Gate/Out-Gate

The rail facility applies a time stamp when the draymen bring a container into the ramp (in-gate) and when they leave the ramp with a container (out-gate). This helps for tracking purposes. - Interchange agreement

This agreement between a railroad and a drayage company allows draymen to pick up and drop off intermodal equipment at the specified railroad facility. - Notification

When a loaded container arrives at the destination rail facility, the railroad will pull it off the train and place it on a chassis. Once the loaded container is placed on a chassis, the rail sends a notification to the draymen and the intermodal provider, alerting them that the container is ready for final delivery. - Per Diem

Also called demurrage, this is a daily fee applied to containers when they are not on the train. Often times, the intermodal provider will either cover this or bake it into their rates, and the shipper will not actually see the charge. However, it is important to understand how your intermodal provider approaches per diem in their accessorial schedule. - Railbill

This is the (electronic) paperwork that the intermodal provider sends to the railroad, telling them what container is coming, what’s in it, where it needs to go and who is going to pick it up at destination. - Rail Interchange

For longer shipments (e.g. transcontinental), your product will have to transfer across two railroads. This switch is called an interchange. There are steel-wheel interchanges (container stays on the track) and rubber-wheel interchanges (a drayman drives it a short distance across town). Neither shippers nor intermodal providers handle this — the railroads take care of everything. - Ramp

This is the most common name for an intermodal terminal. - TOFC

This is the abbreviation for Trailer on Flatcar. Not all intermodal shipments are in containers (COFC). Sometimes, dry van trailers are lifted right onto the train. TOFC is less common than container shipping, as container stacking allows for twice the freight on a single train.

Getting Ready for Shipping on the Rail

Intermodal opens up capacity, protects your budget, and reduces your shipping carbon footprint. And service is only getting better — all Class I railroads are continually investing in intermodal infrastructure and service improvements.

Though it is not the solution for every lane, it’s an important component of any shipper’s strategy.

Now that you’ve learned:

…the three parts of an intermodal shipment, and how to identify opportunities in your network:

- Origin drayage (road)

- Rail linehaul (rail)

- Destination drayage (road)

…the key benefits of intermodal shipping:

- Cost-savings

- Sustainability

- Increased capacity

…and the four types of intermodal providers, and how to mix them into your strategy:

- Non-asset-based carrier (IMC)

- Asset-based carrier

- Asset-lite carrier

- Reseller

…you’re ready to take the next step.

Learn the four key things every shipper should know before shipping their freight intermodal, and what your responsibilities are in this article on intermodal transportation vs. full truckload.